-

Other audit services

We help clients with the application and use of foreign financial aid of EU and other funds and help prepare financial reports.

-

Audit calculator

The calculator will answer if the company's sales revenue, assets or number of employees exceed the limit of an inspection or audit.

-

Payroll and related services

We perform payroll accounting for companies whether they employ a few or hundreds of employees.

-

Tax accounting

Grant Thornton Baltic's experienced tax specialists support accountants and offer reasonable and practical solutions.

-

Reporting

We prepare annual reports in a timely manner. We help to prepare management reports and various mandatory reports.

-

Consolidation of financial statements

Our experienced accountants and advisors help you prepare consolidation tables and make the consolidation process more efficient.

-

Consultancy and temporary staff

Our experienced specialists advise on more complex accounting transactions, rectify poor historic accounting, and offer the temporary replacement of an accountant.

-

Outsourced CFO service

Our CFO service is suitable for companies of all sizes and in all industries. We offer services to our clients in the required amount and competences.

-

Assessment of accounting processes

We help companies to implement accounting practices that are in compliance with local and international standards.

-

Accounting services for small businesses

We offer affordable service for small businesses. We help organize processes as smartly and cost-effectively as possible.

-

Cryptocurrency accounting

We keep up with blockchain technology to serve and advise crypto companies. We are supported by a network of colleagues in 130 countries.

-

Trainings and seminars

Our accountants have experience in all matters related to accounting and reporting. We offer our clients professional training according to their needs.

-

Business advisory

We offer legal support to both start-ups and expanding companies, making sure that all legal steps are well thought out in detail.

-

Fintech advisory

Our specialists advise payment institutions, virtual currency service providers and financial institutions.

-

Corporate advisory

We advise on legal, tax and financial matters necessary for better management of the company's legal or organizational structure.

-

Transaction advisory

We provide advice in all aspects of the transaction process.

-

Legal due diligence

We thoroughly analyze the internal documents, legal relations, and business compliance of the company to be merged or acquired.

-

In-house lawyer service

The service is intended for entrepreneurs who are looking for a reliable partner to solve the company's day-to-day legal issues.

-

The contact person service

We offer a contact person service to Estonian companies with a board located abroad.

-

Training

We organize both public trainings and tailor made trainings ordered by clients on current legal and tax issues.

-

Whistleblower channel

At Grant Thornton Baltic, we believe that a well-designed and effective reporting channel is an efficient way of achieving trustworthiness.

-

Business model or strategy renewal

In order to be successful, every company, regardless of the size of the organization, must have a clear strategy, ie know where the whole team is heading.

-

Marketing and brand strategy; creation and updating of the client management system

We support you in updating your marketing and brand strategy and customer management system, so that you can adapt in this time of rapid changes.

-

Coaching and development support

A good organizational culture is like a trump card for a company. We guide you how to collect trump cards!

-

Digital services

Today, the question is not whether to digitize, but how to do it. We help you develop and implement smart digital solutions.

-

Sales organisation development

Our mission is to improve our customers' business results by choosing the right focuses and providing a clear and systematic path to a solution.

-

Business plan development

A good business plan is a guide and management tool for an entrepreneur, a source of information for financial institutions and potential investors to make financial decisions.

-

Due diligence

We perform due diligence so that investors can get a thorough overview of the company before the planned purchase transaction.

-

Mergers and acquisitions

We provide advice in all aspects of the transaction process.

-

Valuation services

We estimate the company's market value, asset value and other asset groups based on internationally accepted methodology.

-

Forensic expert services

Our experienced, nationally recognized forensic experts provide assessments in the economic and financial field.

-

Business plans and financial forecasts

The lack of planning and control of cash resources is the reason often given for the failure of many businesses. We help you prepare proper forecasts to reduce business risks.

-

Outsourced CFO service

Our CFO service is suitable for companies of all sizes and in all industries. We offer services to our clients in the required amount and competences.

-

Reorganization

Our experienced reorganizers offer ways to overcome the company's economic difficulties and restore liquidity in order to manage sustainably in the future.

-

Restructuring and reorganisation

We offer individual complete solutions for reorganizing the structure of companies.

-

Corporate taxation

We advise on all matters related to corporate taxation.

-

Value added tax and other indirect taxes

We have extensive knowledge in the field of VAT, excise duties and customs, both on the national and international level.

-

International taxation

We advise on foreign tax systems and international tax regulations, including the requirements of cross-border reporting.

-

Transfer pricing

We help plan and document all aspects of a company's transfer pricing strategy.

-

Taxation of transactions

We plan the tax consequences of a company's acquisition, transfer, refinancing, restructuring, and listing of bonds or shares.

-

Taxation of employees in cross-border operations

An employee of an Estonian company abroad and an employee of a foreign company in Estonia - we advise on tax rules.

-

Tax risk audit

We perform a risk audit that helps diagnose and limit tax risks and optimize tax obligations.

-

Representing the client in Tax Board

We prevent tax problems and ensure smooth communication with the Tax and Customs Board.

-

Taxation of private individuals

We advise individuals on personal income taxation issues and, represent the client in communication with the Tax and Customs Board.

-

Pan-Baltic tax system comparison

Our tax specialists have prepared a comparison of the tax systems of the Baltic countries regarding the taxation of companies and individuals.

-

Internal audit

We assist you in performing the internal audit function, performing internal audits and advisory work, evaluating governance, and conducting training.

-

Internal Audit in the Financial Services Sector

We provide internal audit services to financial sector companies. We can support the creation of an internal audit function already when applying for a sectoral activity license.

-

Audit of projects

We conduct audits of projects that have received European Union funds, state aid, foreign aid, or other grants.

-

Prevention of money laundering

We help to prepare a money laundering risk assessment and efficient anti-money laundering procedures, conduct internal audits and training.

-

Risk assessment and risk management

We advise you on conducting a risk assessment and setting up a risk management system.

-

Custom tasks

At the request of the client, we perform audits, inspections and analyzes with a specific purpose and scope.

-

External Quality Assessment of the Internal Audit Activity

We conduct an external evaluation of the quality of the internal audit or provide independent assurance on the self-assessment.

-

Whistleblowing and reporting misconduct

We can help build the whistleblowing system, from implementation, internal repairs and staff training to the creation of a reporting channel and case management.

-

Information security management

We provide you with an information security management service that will optimise resources, give you an overview of the security situation and ensure compliance with the legislation and standards.

-

Information security roadmap

We analyse your organisation to understand which standards or regulations apply to your activities, identify any gaps and make proposals to fix them.

-

Internal audit of information security

Our specialists help detect and correct information security deficiencies by verifying an organization's compliance with legislation and standards.

-

Third party management

Our specialists help reduce the risks associated with using services provided by third parties.

-

Information security training

We offer various training and awareness building programmes to ensure that all parties are well aware of the information security requirements, their responsibilities when choosing a service provider and their potential risks.

-

Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA)

We will help you create a DORA implementation model that meets your company's needs and ensures that you meet the January 2025 deadline.

-

ESG advisory

We help solve issues related to the environment, social capital, employees, business model and good management practices.

-

ESG audit

Our auditors review and certify sustainability reports in line with international standards.

-

Sustainable investments

We help investors conduct analysis of companies they’re interested in, examining environmental topics, corporate social responsibility and good governance practices.

-

Sustainable tax behaviour

Our international taxation specialists define the concept of sustainable tax behaviour and offer services for sustainable tax practices.

-

ESG manager service

Your company doesn’t necessarily need an in-house ESG manager. This role can also be outsourced as a service.

-

Recruitment services – personnel search

We help fill positions in your company with competent and dedicated employees who help realize the company's strategic goals.

-

Recruitment support services

Support services help to determine whether the candidates match the company's expectations. The most used support services are candidate testing and evaluation.

-

Implementation of human resource management processes

We either assume a full control of the launch of processes related to HR management, or we are a supportive advisory partner for the HR manager.

-

Audit of HR management processes

We map the HR management processes and provide an overview of how to assess the health of the organization from the HR management perspective.

-

HR Documentation and Operating Model Advisory Services work

We support companies in setting up HR documentation and operational processes with a necessary quality.

-

Employee Surveys

We help to carry out goal-oriented and high-quality employee surveys. We analyse the results, make reports, and draw conclusions.

-

HR Management outsourcing

We offer both temporary and permanent/long-term HR manager services to companies.

-

Digital strategy

We help assess the digital maturity of your organization, create a strategy that matches your needs and capabilities, and develop key metrics.

-

Intelligent automation

We aid you in determining your business’ needs and opportunities, as well as model the business processes to provide the best user experience and efficiency.

-

Business Intelligence

Our team of experienced business analysts will help you get a grip on your data by mapping and structuring all the data available.

-

Cybersecurity

A proactive cyber strategy delivers you peace of mind, allowing you to focus on realising your company’s growth potential.

-

Innovation as a Service

On average, one in four projects fails and one in two needs changes. We help manage the innovation of your company's digital solutions!

This year is the point where the economy peaked – it can’t get any better. We already see economic growth tapering off in Estonia, the EU and elsewhere. But will we lose our footing as we slide downhill or will we be able to softly glissade down the easy slopes?

The International Monetary Fund’s overview of the state of the world’s economy predicts that the economy will not continue growing at its current pace. Eurostat data on EU economic growth in Q2 show that GDP grew 2.2% compared to the same period last year, which means that the growth rate has slowed. The Bank of Estonia is calling for 3.5% growth this year, 3.6% next year and 2.5% in 2020.

Populism and trade war breed caution

For business people, the news of the slowdown in growth has also arrived. The results of a recent study by accounting and business advisory company Grant Thornton conducted among 3,500 companies in 35 countries show that while for the last two years, optimism had been consistently increasing among the business community in regard to their outlook for their own company and their country’s economy, the optimism index saw a downturn this Q2. In spite of the fact that entrepreneurs are not particularly worried – 59% of those surveyed said they believed their turnover would increase in the next 12 months – they are still more cautious now, as the economic climate is being negatively influenced by political instability. “Trade war” is the main keyword here, but so is populism, which may have a faster and stronger effect on the economy than we can currently forecast.

The increased cautiousness among entrepreneurs may lead to deepening of a negative tendency. Namely, investments have not been made at the same pace as economic growth. Unfortunately, Estonian companies stand out in this regard, being under the EU average. However, investments are critical for companies to be able to maintain sustainable growth.

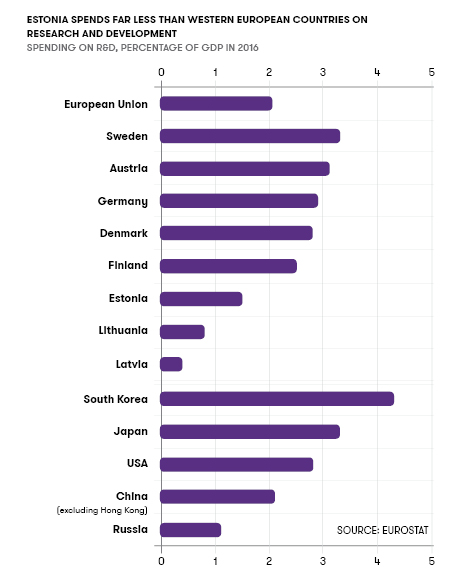

Promoting innovation in words alone

Looking at the distribution of companies’ investments, we see that Estonia’s situation is particularly odd. On one hand, we are building an international image as an innovative digital society. On the other hand, of the already low total investment by companies, under one-third is spent on training people and R&D, while the rest is invested into equipment and machinery (source: a Tallinn University of Technology study on whether corporate investments will attain productivity).

Yet R&D is exactly the magic bullet that can support innovation as we come up with innovative goods and services by rethinking the way work is done and training employees. This is the basic building block of ensuring economic growth and increasing productivity.

The state, too, can – and should – support companies’ investments into R&D. One way to do so is to institute taxation measures, such as tax breaks. True, Estonia offers income tax exemptions for investments but compared to buying machinery, R&D is a long-term investment that will generate a return only years later.

Considering that the general election will take place this coming spring, we will soon see parties tumbling over one another to dispense generous promises. I advise entrepreneurs to also follow the debate from the perspective of what will be pledged by whom for incentivising investments, particularly investments into R&D.

Once every quarter, Grant Thornton International Business Report (IBR) surveys business people in 35 countries to find out their expectations about their country’s economy and their business. The data on optimism in the business community were collected from more than 2,500 executives in May and June 2018.